Mind the Gap: King-Crane Suppressed

More than 400 students of Oberlin College volunteered for duty in the First World War.

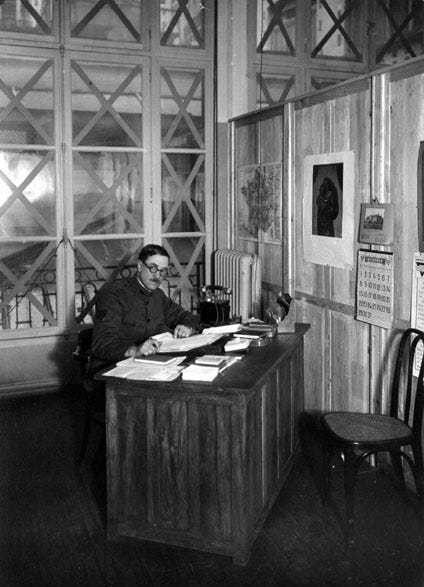

Their President, Henry Churchill King, took leave from the Presidency in the Spring of 1918 to assume the position in Paris as Chairman of the Religious Work Division of the Y.M.C.A. With the end of the war in the Spring of 1919, King was preparing for a return to Oberlin. Love/Artz recount the evolving setting.

From Love’s Henry Churchill King of Oberlin p.p. 215-218: (Henry Churchill King of Oberlin, By Donald M. Love. Yale University press, 1956) (Archive.org library link)

The date of the President's return was actually determined by factors unforeseen in the early spring of 1919. Since the first of the year President Wilson had been interested in sending an Inter-Allied Commission to Syria to study and recommend to the Peace Conference what should be done with the peoples and lands of the former Ottoman Empire. Ray Stannard Baker suggested to Wilson that King would be an excellent chairman for such a Commission […] It was the twenty-sixth of March, and King had been ready to sail for home on April 12, but he canceled his reservations and immediately began to study the demands of the new job if it should materialize.

There followed two full months of uncertainty as to whether the Commission would go and just what sort of Commission it would be. Wilson's plan was for a body representing England, France, Italy, and the United States, with two commissioners from each nation, which should go out to Syria and make a first-hand, on-the-ground investigation of the situation so that an intelligent settlement could be reached. The Supreme Council accepted his plan on March 25, but some of the member nations then proceeded to sabotage the plan by the simple expedient of failing to appoint commissioners. The explanation is to be found in the existence of a large number of secret agreements of long standing among the Allies as to what they would do with the coveted and valuable Turkish area if and when it should fall into their hands. Some of these agreements had included Tsarist Russia, and consequently the interest of the surviving members of the Entente was in the possible distribution of Russia's share as well as in the retention of their own. In any case they saw little to be gained and much to be lost in any such impartial investigation as Wilson contemplated. King's position on the Commission to which he was appointed was analogous to that of Wilson on the Commission to Negotiate Peace. Both were honest men proceeding on the seemingly simple and reasonable thesis that, if open covenants could be openly arrived at, the result would be satisfactory. The difficulty for both was that too much had been done under cover previously and too many commitments had been made, tying hands which should have been free and unselfish agents in administering the future of vast populations who without them could find representation only through their already compromised governments or through regimes arbitrarily imposed upon them.

The problem for President Wilson was to get the Allies to appoint their commissioners. As they delayed, or finally failed to act at all, he faced the problem of whether it was wise to send the Americans to Syria alone. So unlikely did this seem that on Easter Sunday, April 20, King wrote home that he had reservations to sail from Marseilles on the twenty-fourth for New York. Two days later, however, he wrote again that the Commission was to go to Syria after all. On the twenty-seventh he moved into the Hotel Crillon, to be directly associated with the American Commission to Negotiate Peace and to prepare intensively for the work of the Commission on Mandates in Turkey.

The personnel of the American Section of the Commission was speedily arranged, to consist of President King and Mr. Charles R. Crane, afterward Ambassador to China, as commissioners, […] A spurt of activity on the part of England, prompted by an urgent telegram from General Allenby, resulted in the appointment of a distinguished representation, who, however, never got beyond Paris. The British commissioners were to have been Sir Henry McMahon, former High Commissioner in Egypt, and Commander David S. Hogarth, an authority on the Near and Middle East, with Professor Arnold J. Toynbee as Secretary. Neither France nor Italy appointed representatives.

Two special groups were exerting considerable pressure on President Wilson. The Zionists, through Professor Felix Frankfurter, were opposing sending the Commission at all, ostensibly because its findings would possibly delay the final peace beyond the time President Wilson could spend in Paris but really because they feared that those findings might prove contrary to the Balfour Declaration of November, 1917, favoring a Jewish "National Home." The Arabs, through the Emir Feisal, confident that only through such an investigation as Wilson planned could their point of view be adequately presented, were urging the immediate sending of the Commission, whether Inter-Allied or simply American. On May 22, President King, Mr. Crane, and Professor W. L. Westerman, Chief of the Western Asia (Turkish) Division of the American Commission to Negotiate Peace, called on President Wilson and secured his assurance that the investigation would be made, and at once.

An excellent summary of the work of the Commission appeared in an article in the Moslem World for April, 1942, under the title: "An American Experiment in Peace Making: The King-Crane Commission." It was written by Professor Harry N. Howard, then of Miami University, later Chief of the Near East Research Branch of the Department of State and United Nations Adviser on Near Eastern, South Asian, and African Affairs. Essential facts have been freely drawn from this source and from the Report of the Commission, finally published in Editor and Publisher for December 2, 1922, with the subheading: "A Suppressed Official Document of the United States Government."

The Commission arrived in Palestine on June 10, 1919, after a brief stopover in Constantinople and proceeded at once to its work. The method pursued is thus described in the Report:

“to meet in conference individuals and delegations who should represent all the significant groups in the various communities, and so to obtain as far as possible the opinions and desires of the whole people. The process itself was inevitably a kind of political education for the people, and, besides actually bringing out the desires of the people, had at least further value in the simple consciousness that their wishes were being sought. We were not blind to the fact that there was considerable propaganda; that often much pressure was put upon individuals and groups; that sometimes delegations were prevented from reaching the Commission; and that the representative authority of many petitions was questionable. But the Commission believes that these anomalous elements in the petitions tend to cancel one another when the whole country is taken into account, and that, as in the composite photograph, certain great common emphases are unmistakable.”

The important towns of the area were visited by the Commission, representatives of about 1,500 villages appeared before it, and some 1,863 petitions, with approximately 19,000 signatures, were presented and considered. Certainly there was no lack of thoroughness in the investigation. The special force of the ultimate recommendations of the Commission lay in the fact that they were based not only upon careful preliminary studies which had been made in Paris but also upon this conscientious and painstaking examination of public opinion in the actual areas concerned.

This is what King said about Syria/Palestine:

The American Section of the International Commission on Mandates in Turkey, in order that their mission may be clearly understood are furnishing to the press the following statement, which is intended to define as accurately as possible the nature of their task, as given to them by President Wilson.

The American people-having no political ambitions in Europe or the Near East; preferring, if that were possible, to keep clear of all European, Asian, or African entanglements but nevertheless sincerely desiring that the most permanent peace and the largest results for humanity shall come out of this war- recognize that they cannot altogether avoid responsibility for just settlements among the nations following the war, and under the League of Nations. In that spirit they approach the problems of the Near East.

[….]

'Certain communities formerly belonging to the Turkish Empire have reached a stage of development where their existence as independent nations can be provisionally recognized subject to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by a Mandatory until such time as they are able to stand alone. The wishes of these communities must be a principal consideration in the selection of the Mandatory.'

[…..]

An estimate of the population of the different districts is added at this point, for a better understanding of the tables and discussion which follow. The figures in all cases must be regarded as only approximate, but may be taken as giving a fairly accurate view of the proportions of the population.

[…]

E-Zionism

1-2-3. The petitions favoring the Zionist program have been analyzed above in the discussion of programs. In opposition to these are the 1,350 (72.3 per cent) petitions protesting against Zionist claims and purposes. This is the third largest number for any one point and represents a more widespread general opinion among both Moslems and Christians than any other. The anti-Zionist note was especially strong in Palestine, where 222 (85.3 per cent) of the 260 petitions declared against the Zionist program. This is the largest percentage in the district for any one point.

4. Zionism.-The Jews of Palestine declared themselves unanimously in favor of the Zionistic scheme in general, though they showed difference of opinion in regard to the details and the process of its realization. The elements of agreement may be stated as follows:

(a) Palestine, with a fairly large area, to be set aside at once as a "national home" for the Jews.

(b) Sooner or later the political rule of the land will become organized as a "Jewish Commonwealth,"

(c) At the start authorization will be given for the free immigration of Jews from any part of the world; for the unrestricted purchase of land by the Jews, and for the recognition of Hebrew as an official language.

(d) Great Britain will be the mandatory power over Palestine, protecting the Jews and furthering the realization of the scheme.

(e) The Great Powers of the world have declared in favor of the scheme, which merely awaits execution.

Differences exist especially along two lines:

(a) Whether the Jewish Commonwealth should be set up soon or after a considerable lapse of time.

(b) Whether the chief emphasis should be upon a restoration of the ancient mode of life, ritual, exclusiveness and particularism of the Jews, or upon economic development in a thoroughly modern fashion, with afforestation, electrification of water-power, and general full utilization of resources.

…

ZIONISM

E. We recommend, in the fifth place, serious modification of the extreme Zionist program for Palestine of unlimited immigration of Jews, looking finally to making Palestine distinctly a Jewish State.

(1) The Commissioners began their study of Zionism with minds predisposed in its favor, but the actual facts in Palestine, coupled with the force of the general principles proclaimed by the Allies and accepted by the Syrians have driven them to the recommendation here made.

(2) The commission was abundantly supplied with literature on the Zionist program by the Zionist Commission to Palestine; heard in conferences much concerning the Zionist colonies and their claims; and personally saw something of what had been accomplished. They found much to approve in the aspirations and plans of the Zionists, and had warm appreciation for the devotion of many of the colonists and for their success, by modern methods, in overcoming natural obstacles.

(3) The Commission recognized also that definite encouragement had been given to the Zionists by the Allies in Mr. Balfour's often quoted statement in its approval by other representatives of the Allies. If, however, the strict terms of the Balfour Statement are adhered to -favoring "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people," "it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights existing in non-Jewish communities in Palestine"-it can hardly be doubted that the extreme Zionist Program must be greatly modified.

For "a national home for the Jewish people" is not equivalent to making Palestine into a Jewish State; nor can the erection of such a Jewish State be accomplished without the gravest trespass upon the "civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine." The fact came out repeatedly in the Commission's conference with Jewish representatives, that the Zionists looked forward to a practically complete dispossession of the present non-Jewish inhabitants of Palestine, by various forms of purchase.

In his address of July 4, 1918, President Wilson laid down the following principle as one of the four great "ends for which the associated peoples of the world were fighting"; "The settlement of every question, whether of territory, of sovereignty, of economic arrangement, or of political relationship upon the basis of the free acceptance of that settlement by the people immediately concerned and not upon the basis of the material interest or advantage of any other nation or people which may desire a different settlement for the sake of its own exterior influence or mastery." If that principle is to rule, and so the wishes of Palestine's population are to be decisive as to what is to be done with Palestine, then it is to be remembered that the non-Jewish population of Palestine-nearly nine tenths of the whole-are emphatically against the entire Zionist program. The tables show that there was no one thing upon which the population of Palestine were more agreed than upon this. To subject a people so minded to unlimited Jewish immigration, and to steady financial and social pressure to surrender the land, would be a gross violation of the principle just quoted, and of the people's rights, though it kept within the forms of law

It is to be noted also that the feeling against the Zionist program is not confined to Palestine, but shared very generally by the people throughout Syria as our conferences clearly showed. More than 72 per cent-1,350 in all-of all the petitions in the whole of Syria were directed against the Zionist program. Only two requests-those for a united Syria and for independence-had a larger support This genera] feeling was only voiced by the "General Syrian Congress," in the seventh, eighth and tenth resolutions of the statement. (Already quoted in the report.)

The Peace Conference should not shut its eyes to the fact that the anti-Zionist feeling in Palestine and Syria is intense and not lightly to be flouted. No British officer, consulted by the Commissioners, believed that the Zionist program could be carried out except by force of arms. The officers generally thought that a force of not less than 50,000 soldiers would be required even to initiate the program. That of itself is evidence of a strong sense of the injustice of the Zionist program, on the part of the non-Jewish populations of Palestine and Syria. Decisions, requiring armies to carry out, are sometimes necessary, but they are surely not gratuitously to be taken in the interests of a serious injustice. For the initial claim, often submitted by Zionist representatives, that they have a "right" to Palestine, based on an occupation of 2,000 years ago, can hardly be seriously considered.

There is a further consideration that cannot justly be ignored, if the world is to look forward to Palestine becoming a definitely Jewish state, however gradually that may take place. That consideration grows out of the fact that Palestine is "the Holy Land" for Jews, Christians, and Moslems alike. Millions of Christians and Moslems all over the world are quite as much concerned as the Jews with conditions in Palestine especially with those conditions which touch upon religious feeling and rights. The relations in these matters in Palestine are most delicate and difficult. With the best possible intentions, it may be doubted whether the Jews could possibly seem to either Christians or Moslems proper guardians of the holy places, or custodians of the Holy Land as a whole.

The reason is this: The places which are most sacred to Christians-those having to do with Jesus-and which are also sacred to Moslems, are not only not sacred to Jews, but abhorrent to them. It is simply impossible, under those circumstances, for Moslems and Christians to feel satisfied to have these places in Jewish hands, or under the custody of Jews. There are still other places about which Moslems must have the same feeling. In fact, from this point of view, the Moslems, just because the sacred places of all three religions are sacred to them have made very naturally much more satisfactory custodians of the holy places than the Jews could be. It must be believed that the precise meaning, in this respect, of the complete Jewish occupation of Palestine has not been fully sensed by those who urge the extreme Zionist program. For it would intensify, with a certainty like fate, the anti-Jewish feeling both in Palestine and in all other portions of the world which look to Palestine as "the Holy Land."

In view of all these considerations, and with a deep sense of sympathy for the Jewish cause, the Commissioners feel bound to recommend that only a greatly reduced Zionist program be attempted by the Peace Conference, and even that, only very gradually initiated. This would have to mean that Jewish immigration should be definitely limited, and that the project for making Palestine distinctly a Jewish commonwealth should be given up.

There would then be no reason why Palestine could not be included in a united Syrian State, just as other portions of the country, the holy places being cared for by an International and Inter-religious Commission, somewhat as at present under the oversight and approval of the Mandatary and of the League of Nations. The Jews, of course, would have representation upon this Commission.

The recommendations now made lead naturally to the necessity of recommending what power shall undertake the single Mandate for all Syria.

(1) The considerations already dealt with suggest the qualifications, ideally to be desired in this Mandatary Power: First of all it should be freely desired by the people. It should be willing to enter heartily into the spirit of the mandatary system, and its possible gift to the world, and so be willing to withdraw after a reasonable period, and not seek selfishly to exploit the country. It should have a passion for democracy, for the education of the common people and for the development of national spirit. It needs unlimited sympathy and patience in what is practically certain to be a rather thankless task, for no Power can go in honestly to face actual conditions (like land-ownership, for example) and seek to correct these conditions, without making many enemies. It should have experience in dealing with less developed peoples, and abundant resources in men and money.

(2) Probably no Power combines all these qualifications, certainly not in equal degree. But there is hardly one of these qualifications that has not been more or less definitely indicated in our conferences with the Syrian people and they certainly suggest a new stage in the development of the self-sacrificing spirit in the relations of peoples to one another. The Power that undertakes the single mandate for all Syria, in the spirit of these qualifications will have the possibility of greatly serving not only Syria but the world, and of exalting at the same time its own national life. For it would be working in direct line with the high aims of the Allies in the war, and give proof that those high aims had not been abandoned. And that would mean very much just now, in enabling the nations to keep their faith in one another and in their own highest ideals.

(3) The Resolutions of the Peace Conference of January 30, 1919, quoted in our instructions, expressly state for regions to be "completely severed from the Turkish Empire," that "the wishes of these communities must be a principal consideration in the selection of the Mandatory Power." Our survey left no room for doubt of the choice of the majority of the Syrian people. Although it was not known whether America would take a mandate at all; and although the Commission could not only give no assurances upon that point, but had rather to discourage expectation; nevertheless, upon the face of the returns, America was the first choice of 1,152 of the petitions presented-more than 60 per cent-while no other Power had as much as 15 per cent for first choice.

And the conferences showed that the people knew the grounds upon which they registered their choice for America. They declared that their choice was due to knowledge of America's record, the unselfish aims with which she had come into the war, the faith in her felt by multitudes of Syrians who had been in America; the spirit revealed in American educational institutions in Syria, especially the College in Beirut, with its well known and constant encouragement of Syrian national sentiment, their belief that America had no territorial or colonial ambitions, and would willingly withdraw when the Syrian state was well established as her treatment both of Cuba and the Philippines seemed to them to illustrate; her genuinely democratic spirit, and her ample resources.

From the point of view of the desires of the "people concerned," the Mandate should clearly go to America.

(4) From the point of view of qualifications, too, already stated as needed in the Mandatary for Syria, America as first choice of the people, probably need not fear careful testing, point by point, by the standard involved in our discussion of qualifications, though she has much less experience in such work than Great Britain, and is likely to show less patience and though her definite connections with Syria have been less numerous and close than those of France. She would have at least the great qualification of fervent belief in the new mandatary system of the League of Nations, as indicating the proper relations which a strong nation should take toward a weaker one. And though she would undertake the mandate with reluctance, she could probably be brought to see, how logically the taking of such responsibility follows from the purposes with which she entered the war and from her advocacy of the League of Nations.

(5) There is the further consideration that America could probably come into the Syrian situation, in the beginning at least, with less friction than any other Power. The great majority of Syrian people, as has been seen, favor her coming, rather than that of any other power. Both the British and the French would find it easier to yield their respective claims to America than to each other. She would have no rival imperial interests to press. She would have abundant resources for the development of the sound prosperity of Syria, and this would inevitably benefit in a secondary way the nations which have had closest connection with Syria, and so help to keep relations among the Allies cordial. No other Power probably would be more welcome, as a neighbor, to the British, with their large interests in Egypt, Arabia and Mesopotamia; or to the Arabs and Syrians in these regions; or to the French with their long-established and many-sided interests in Beirut and the Lebanon.

(6) The objections to recommending at once a single American Mandate for all Syria are: first of all, that it is not certain that the American people would be willing to take the Mandate- that it is not certain that the British or French would be willing to withdraw, and would cordially welcome America's coming, a situation which might prove steadily harassing to an American administration; that the vague but large encouragement given to the Zionist aims might prove particularly embarrassing to America, on account of her large influential Jewish population- and that if America were to take any mandate at all, and were to take but one mandate, it is probable that an Asia Minor Mandate would be more natural and important. For there is a task there of such peculiar and worldwide significance as to appeal to the best in America, and demand the utmost from her, and as certainly to justify her in breaking with her established policy concerning mixing in the affairs of the Eastern hemisphere. The Commissioners believe, moreover, that no other Power could come into Asia Minor, with hands so free to give impartial justice to all the peoples concerned.

To these objections as a whole, it is to be said, that they are all of such a kind that they may resolve themselves; and that they only form the sort of obstacles that must be expected, in so large and significant an undertaking. In any case they do not relieve the Commissioners from the duty of recommending the course which, in their honest judgment, is the best courses and the one for which the whole situation calls.

The suppression of the King-Crane Report was a crime against humanity’s right to know the facts that were promised by Woodrow Wilson to govern the disposition of political power and national aspiration. It was simultaneously a betrayal of the principles upon which millions of men had laid down their lives. That crime and that betrayal reveal a constant in Zionist existence: the need and capacity to deceive, to suppress facts, to create illusion, to control your thoughts.

The suppression was something more: a signal from the most authoritative source in the world of American allegiance to British Imperial Design, recast now as “The Rules Based Order.”

The false narrative created by the suppression lives today in the control of news surrounding the latest war over Zionism and even in the British flavored defense of Israel before the International Court of Justice by Professor Malcolm Shaw in the first two minutes of his presentation, beginning at 34:20.

In our next posting let’s observe the way in which, western imperial design, with American leadership since 1946, has corrupted Black American sense of justice.